Full Houses: The Popularity of the Korean Drama Full House and its Southeast Asian remakes

Photo Credit: DramaPanda

Full House is a South Korean romantic comedy television series, based on a manhwa of the same name by Won Soo-yeon. The drama aired in 2004 on KBS2, one of the country’s terrestrial broadcasting stations and starred Rain, a prominent idol who was part of the then budding Hallyu Wave, as the famous actor Lee Young Jae, Song Hye Kyo as Han Ji Eun and supporting actors like Han Eun Jung as Kang Hye Won as well as Kim Sung Soo as Yoo Min Hyuk.

The story goes like this:

Photo Credit: Wikipedia

During its run, the drama enjoyed high ratings, peaking at forty-two percent nationwide for its last episode according to the drama’s Wikipedia page:

Refurbishing Full House

The drama’s success within South Korea led to a spin-off or sequel, titled Full House Take 2, in 2012. It was a joint venture by Korean, Chinese and Japanese companies and was loosely based on the original manhwa and 2004 hit.

Photo Credit: SBS Plus

While the drama saw great domestic popularity, its appeal went beyond national borders and touched the hearts of audiences in the rest of Asia and the Western world. A recent article by ReelRundown even lists Full House as one of the “Top 10 Most Popular Korean Dramas”.

The article also gives reasons for the popularity of Korean dramas among Western audiences, namely how the stars are attractive eye candies, the dramas’ fresh cultural appeal, squeaky clean content and format, which interestingly correspond with those mentioned in one of the course readings, “A ‘real’ fantasy: hybridity, Korean drama, and pop cosmopolitans”. The course reading discusses how the beauty of K-dramas’ male protagonists, especially the caring and sensitive aspects of their Asian masculinity offer a fantasy for Western viewers (Lee 371). Furthermore, the “cultural differences and unfamiliarity with foreign media also increase viewers’ fascination with and pleasure gained from them” (Lee 367). Compared to Western counterparts which feature a copious amount of sexuality and violence, K-dramas portray storylines that are “safer, more conservative and relationship-based” (Lee 370). Moreover, the K-dramas’ ability to “make clichés interesting and different” and their unique format, as they “usually last only one season with a set number of episodes”, between sixteen and twenty-four, with a definitive end and a strong sense of conclusion also contribute to their rise in the West (Lee 371-372).

A look at the ReelRundown’s Facebook page will reveal that its authors belong to a community of K-drama ‘experts’ and Lee argues that participation in such online transnational media platforms “helps fans create hybrid, powerful identities by offering opportunities to develop cultural and technical competencies, and fuse different cultural elements and roles in complex ways” (Lee 369).

Besides Western audiences, the Korean drama resonated so well with Asian audiences outside South Korea that some of these Asian countries, who had previously only consumed such Korean content, started to produce their own versions of the drama. Subsequent adaptations of the drama made minor changes to its details but the essential plot points remain the same. According to Variety, Full House has already been remade for four different Asian markets: the Philippines, Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia. There is also a Chinese adaptation made in 2015, starring Eli, a member of South Korean boy group, U-KISS, which still has not seen the light of day as a result of the unspoken ban on Korean TV shows in China after 2016 following the escalation of political tensions and another rumoured remake in 2019 (Park et al. 151).

A KissAsian listing of Full House Thai (2014), a version I really like.

The comments section of the drama listing. It turns out I was not the only one who like the Thai version more than the original.

As a viewer who had inadvertently come across such an adaptation and actually found myself liking it more than the original, I am interested to find out why Full House has been able to appeal to a wide range of audiences with different nationalities across the Asian region and beyond. In fact, it is a question that other scholars like Jeon, recognised as one “well worth addressing” (Jeon 69).This essay thus seeks to examine the factors that led to the drama’s popularity in Asia, particularly in Southeast Asian countries as the drama has inspired numerous remakes in these places.

Government Policies

To explain the strong reception of the drama away from the South Korean peninsula, there is a need to locate the drama in the broader context of Korean broadcasting history (While the term Korean can also mean North Korean cultural producers and products, the term will refer solely to those originating from South Korea for the purpose of this essay.).

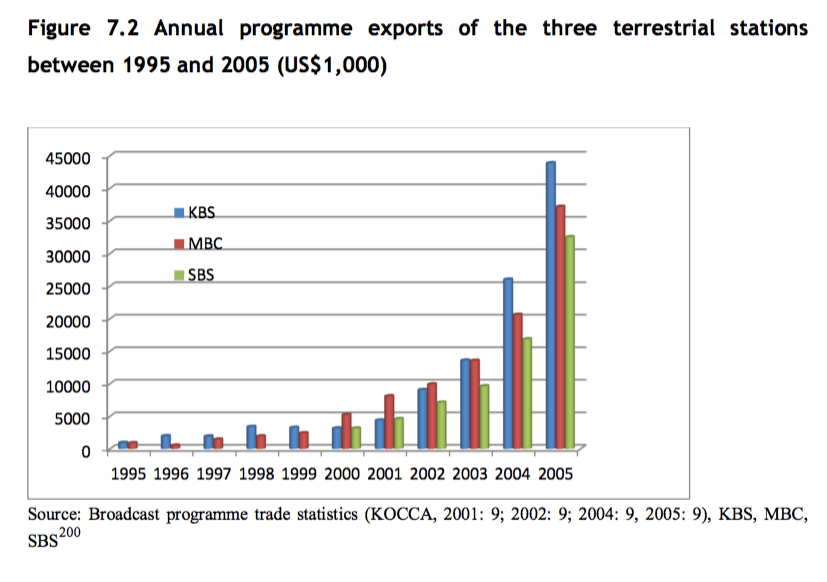

The drama was released during the period of a significant increase in Korean drama exports between 1995 and 2005 (Jeon 12). With a growth of 72.8% over 2004, the export of television dramas represented a 92% (US$101.6 million) share of the total export of media programmes (US$123.4 million) in 2005 (Kim and Wang 428). In 2005, the major importing countries were mainly in Asia, particularly Japan (60.1%), Taiwan (11.4%), China (9.9%) and the Philippines (3.7%). New markets such as Mexico, Brazil, Turkey, Jordan, Tanzania, Cambodia, Mongolia, Uzbekistan and Russia also began to gradually increase their imports of Korean television programmes in 2005 (Kim and Wang 429). From these figures, it is clear that the circulation and popularity of television dramas constitute the nexus of the Hallyu phenomenon, which refers to a new wave of Korean-generated popular cultural products that extends throughout South and East Asia and beyond (Kim and Wang 428).

The Kim Dae-jung regime’s (1998-2003) cultural policies philosophy which notably moved toward deregulation and the promotion of the cultural industries, as well as away from the protection and regulation characteristic of the previous regimes has been related both to the production of high quality dramas and to their export success (Jeon 106-107). The Noh Moo-hyun regime (2003-2007) then established a series of support policies such as financial aid to boost the export of popular cultural products, commonly known as the Korean Wave support policies (Jeon 120).

Consequently, KBS with its “relatively longer history in programme exports than MBC or SBS, the two other terrestrial stations” arguably benefitted the most from the reduced state intervention and support policies as evident from how its annual programme exports were the highest among the three major terrestrial broadcasting stations between 2003 to 2005 (Jeon 101). Full House can therefore be regarded as a beneficiary of these government policies that were instrumental in its export success.

Economic Development and Technological Revolution

The popularity of Full House can also be attributed to the “rapid technical developments [that] have encouraged the Korean broadcasting industry to diversify its production, distribution and consumption of broadcasting content, which has in turn attracted more fragmented audiences” (Jeon 56). Technological advances such as the first digital multimedia broadcasting (DMB) to mobile phones around the globe “has allowed audiences to enjoy television programmes without being limited by time or location” (Jeon 62). Additionally, “[t]he transition from analogue to digital transmission enabled broadcasters to compete with the internet as an additional platform for television programming” (Jeon 56).

Also, to the viewers in Southeast Asian countries, “economically-developed Korean society becomes a model for their future”, thereby explaining their attraction to Korean dramas with their frequent use of images or symbols of economic wealth and modernity like tall skyscrapers (Shim 1).

Drama Tourism

Photo Credit: visitKorea

Since the drama ended, there had been a steady stream of visitors to the “Full House” in Sido Island, over the years, from all over the world before the house was eventually demolished due to irreparable damage sustained from a typhoon (Thornton 1).

Photo Credit: HALO Productions

It is also interesting to note that the drama did not just influence your ordinary tourists to visit South Korea, the production team for the Thai remake of Full House shot ten out of twenty episodes on location in Korea, featuring famous tourist spots like Dongdaemun, Hangang Park and Myeongdong, to name a few (Hong 1). Following the shoot, the staff, including the actors, “still express that they miss Korea”, hinting at a possible revisit intention (Hong 1).

Opportunity To Perform Cultural Hybridity

Full House “plays the role of a cultural mediator that reinterprets and mediates Western popular culture, and transmits it to neighboring countries” (Park et al. 142). For example, while the visuals of the drama remain largely Asian, with Korean faces, the main protagonists held a Western-style wedding instead.

Photo Credit: KBS

Similar to Western fans, Asian fans of the drama engage in the process of negotiating cultural hybridity by becoming producers themselves. The Thais, in their adaptation of FullHouse, showcased elements of Korean culture and Thai culture concurrently.

Aom, the Thai actress playing Song Hye Kyo’s character, was seen wearing a Hanbok in the Thai version of Full House, in what can be supposed to be an attempt to pay homage to the Korean roots of the original drama.

Photo Credit: HALO Productions

The Thai version of Full House featured a Thai-style wedding.

Photo Credit: HALO Productions

Hence, Korean dramas offer a chance for their fans in Southeast Asia to appropriate Korean culture and incorporate their own when producing a local version. This “hybridization of familiarity and difference is an essential aspect of [Korean dramas’] global appeal and reception” (Lee 366).

The Filipino version of Full House instantly hit the number two spot, with a 35% rating, when it was launched on Philippine prime-time television in 2005 (Souza and Mallari 1).

Photo Credit: GMA

Appealing to Asian Sensitivities….

Many scholars also “relied on the notion of cultural proximity to explain the popularity of Korean dramas” (Part et al. 142). Asian values like filial piety feature in Full House as Ji Eun, upon losing her house to Young Jae, the only thing her father left behind for her, worked as Young Jae’s housekeeper to reclaim her inheritance. For her, it was not so much the monetary value of the house she prizes but the emotional connection to her father through her possession of the house.

The Vietnamse version of Full House

Photo Credit: Dorama TV

This trope is consistent throughout the Southeast Asian remakes and the Thai version takes its portrayal of Asian values one step further. Instead of having the female protagonist’s best friends sell her house away, it was her cousin who betrayed her trust in the Thai version. However, the Thai drama creates more sympathy in its viewers because her cousin is shown to have difficulties of her own. There is also an arc where the female protagonist sought to help her cousin overcome her troubles, highlighting the importance of family and thus embodying the old Asian adage, “blood is thicker than water”.

Photo Credit: HALO Productions

The fact that Asian values are emphasised more in the Thai version can also be observed in the scene where the male and female protagonist brought their grandmother out to dance as well as the family dinner scene. In both scenes, family bonding time is shown to be sacred and something to be protected.

Photo Credit: HALO Productions

Photo Credit: HALO Productions

Once again, the importance of family and respect for elders is at the forefront of the Thai drama.

Therefore, the Southeast Asians’ love for K-dramas can be explained with the argument that “audiences who are composed of a broad series of groups, not a homogeneous mass, make an active choice to view, read and interpret visual media texts and images including television in order to produce from them meanings that connect with their own social and cultural values and experiences” (Kim and Wang 438). “While some regard the shared cultural heritage as the basis for the pan-Asian popularity of Korean dramas, others claim that the very consumption of Korean dramas helps construct a sense of Asian identity, by enabling Asian fans to imagine their belonging to an East Asian community.” (Park et al. 142). Regardless of which way the issue is viewed, there can be no doubt that the common Asian values that are portrayed in K-dramas facilitates their acceptance by Asian audiences.

….Or Not

Although Full House appeals to traditional Asian sensibilities, it also propagates more liberal Western values such as cohabitation (under the guise of a contract marriage for the two lead characters). Nonetheless, the Korean drama plays its role as “a cultural mediator” (Park et al. 142).

Full House also subverts conventional Asian gender roles in which women are responsible for housework while men’s work lies in the public domain. The fact that Ji Eun is a homebody while Young Jae is a public figure very much solidifies this dichotomous gender relationship at first. Yet, later in the drama, Young Jae is the one who puts on an apron and picks up cleaning tools.

Photo Credit: KBS

The same happens in the Thai version where the male protagonist, Mike, cross-dresses with a mop in his hand as part of the female protagonist, Aom’s, daydream.

Photo Credit: HALO Productions

Full House thus feeds its viewers with alternative possibilities or fantasies that deviate from the gender roles that are usually depicted on Asian screens.

While it must be acknowledged that the drama still plays to the typical Asian idea of male chivalry by characterising the female protagonist as the damsel in distress, the story is also a Bildungsroman or a coming-of-age tale for the female protagonist. The female protagonist has to prove herself to her male counterpart and those around him (Liew 1). In Full House, Ji Eun is an aspiring writer who is eager to publish her first story and establish herself. As such, she often spends many sleepless nights perfecting her writing and even consults Min Hyuk for advice.

Photo Credit: KBS

Similarly, Aom is hard at work pursuing her dream of becoming an accomplished writer in the Thai version.

Photo Credit: HALO Productions

Even though Full House connects with its Asian audiences through its representation of shared cultural values, it is also popular for defying some of these values and offering its Asian viewers a different worldview that its remakes aim to replicate.

Social Media

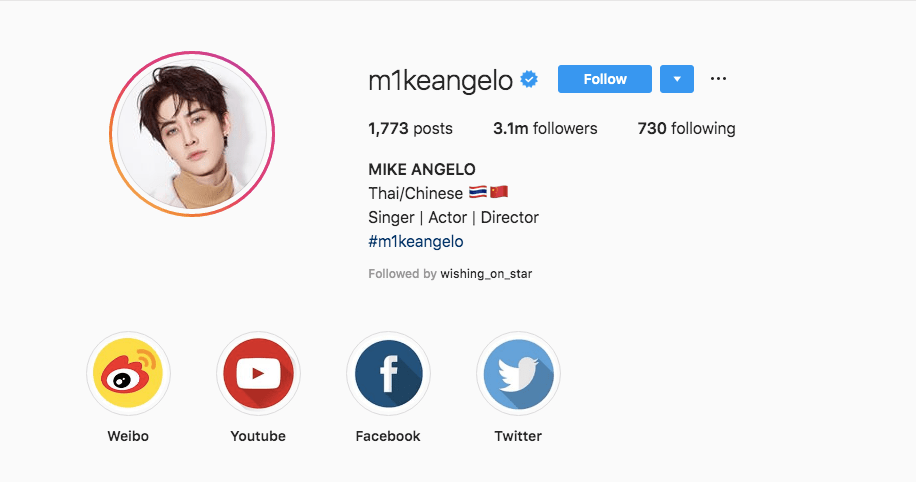

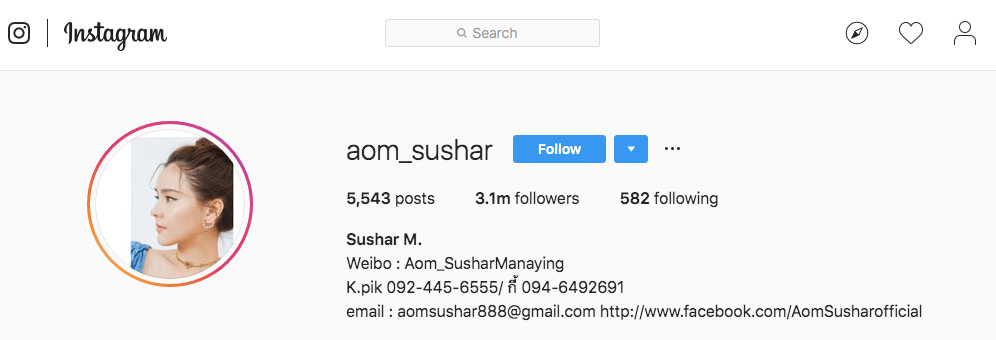

Unfortunately, the use of social media was not prevalent during the heydays of Full House. By 2014, when the Thai remake was completed, the Thai stars shot to fame on various social media platforms such as Weibo and Instagram. Their popularity in China also skyrocketed following the success of the drama and they were invited as guests on Chinese variety shows.

Aomike (the couple ship name) on Generation Show

Photo Credit: ShenZhen TV

Social media is instrumental in promoting a drama to youth audiences especially. As examined in “the historical development of the Hallyu phenomenon in Indonesia”, changes are “in parallel with the rapidly digitali[s]ed mediascape of the country” (Jeong et al. 2301). The popularity of K-dramas like Full House is limited by “a generational difference between the middle-aged group and the younger group in terms of their consumption of transnational cultural products” which causes “disparities in the use of technology between generations (Jeong et al. 2302). Thus, the spread of the drama is subjected to the prevalence of social media and the ability of its audience to harness it to increase the drama’s accessibility.

Full House Revisited

Photo Credit: KBS

In conclusion, the presence of remakes attests to the Korean drama’s enduring resonance with Asian audiences. The South Korean government’s deregulation and support policies for the country’s cultural industries augmented its export success, which was further aided by the technological advancements that helped broaden the reach of Korean dramas. Asian viewers also gravitated to K-dramas as a result of South Korea’s economic development, which provided a model of what they could aspire towards. Furthermore, Full House, with its showcase of cultural hybridity, inspired drama tourism and invited its adaptations to come up with their own combinations of cultural mixes. Moreover, the popularity of Full House can be ascribed to its inclusion of Asian values that speak to its target audiences. Yet, there are also elements that are relatively non-Asian, particularly with the drama’s treatment of gender roles and female agency. Lastly, as seen from the case study of Indonesia, the drama’s popularity is dependent on the extent of social media penetration in its destination markets. There is a tendency for the drama to be more popular among younger audiences rather than older ones as the former is more tech-savvy.

Works Cited

Bacon, Candace. “Why Korean Dramas Are Popular.” ReelRundown, 27 Feb. 2019, reelrundown.com/movies/Korean-Wave-Why-Are-Korean-Dramas-Popular.

“Full House (South Korean TV Series).” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 9 Sept. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Full_House_(South_Korean_TV_series).

Frater, Patrick. “Korean TV Hit ‘Full House’ to Be Remade in China.” Variety, 21 Oct. 2014, variety.com/2014/tv/asia/korean-tv-hit-full-house-to-be-remade-in-china-1201335264/.

Hong, Ji-hee. “Full House, Coming Into Blossom Under the Scorching Sun: A Thai TV Series Remake.” Korean Film Biz Zone, 31 Oct. 2014, http://www.koreanfilm.or.kr/webzine/commBoard/preview.jsp?wbSeq=80&blbdComCd=601020.

Jeon, Won Kyung. The ‘Korean Wave’ and television drama exports, 1995-2005. PhD thesis, University of Glasgow, 5 Sept. 2013.

Jeong, Jae-Seon, Seul-Hi Lee, & Sang-Gil Lee. “When Indonesians Routinely Consume Korean Pop Culture: Revisiting Jakartan Fans of Korean Drama Dae Jang Geum.” International Journal of Communication, vol. 11, no. 20, 2017, pp. 2288-2307., ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/6302.

Kim, Sangkyun, and Hua Wang. “From Television to the Film Set: Korean Drama Daejanggeum Drives Chinese, Taiwanese, Japanese and Thai Audiences to Screen-Tourism.” International Communication Gazette, vol. 74, no. 5, 2012, pp. 423–442., doi:10.1177/1748048512445152.

Lee, Hyunji. “A ‘Real’ Fantasy: Hybridity, Korean Drama, and Pop Cosmopolitans.” Media, Culture & Society, vol. 40, no. 3, Nov. 2017, pp. 365–380., doi:10.1177/0163443717718926.

Liew, Kai Khiun. “Commentary: Southeast Asia’s Romance with Korean Drama Shows.” CNA, 11 July 2017, http://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asia/commentary-southeast-asia-s-romance-with-korean-drama-shows-9021166.

Park, Ji Hoon, et al. “The Rise and Fall of Korean Drama Export to China: The History of State Regulation of Korean Dramas in China.” International Communication Gazette, vol. 81, no. 2, Nov. 2018, pp. 139–157., doi:10.1177/1748048518802915.

Shim, Doobo et al. “Riding the Korean Wave in Southeast Asia.” Fair Observer, 24 May 2017, www.fairobserver.com/region/asia_pacific/korean-wave-k-pop-culture-southeast-asia-news-45109/.

Souza, Damian de, and Rene Mallari. “Full houses: Korean drama is enjoying “phenomenal” success in the Philippines. And the new formats for success are not being lost on local producers or Latin American telenovela distributors.” Television Asia, 1 May 2005.

Thornton, Stephe. “End of an Asian Icon: The ‘Full House’ Set on Sido Island Is No More.” Cloud USA, 24 June 2013, cloudusa.blog/2013/06/24/end-of-an-asian-icon-the-full-house-set-on-sido-island-is-no-more/.